Civil Rights Act Helps Break Sports Boundaries

Fifty years ago, a landmark piece of legislation opened doors for minorities and women, and people like Jerry Gaines, John Dobbins and Anne and Lynne Jones became pioneers at Tech, showing the way for those coming behind them

December 17, 2014

By Jimmy Robertson

(The following story appeared in the November issue of Inside Hokie Sports.)

BREAKING DOWN BARRIERS

Here is a timeline of some important dates in Virginia Tech history, most of which, but not all, relate to athletics:

1921 – Women first enroll as full-time students

1923 – Mary Brumfield becomes the first woman to receive a degree from Tech

1953 – Irving Linwood Peddrew, III becomes the first black student admitted to Tech

1958 – Charlie L. Yates becomes the first black graduate at Tech, receiving a B.S. in mechanical engineering

1966 – Linda Adams, Jacquelyn Butler, Linda Edmonds, Freddie Hairston, Marguerite Harper, and Chiquita Hudson becomes the first black females to enroll at Tech

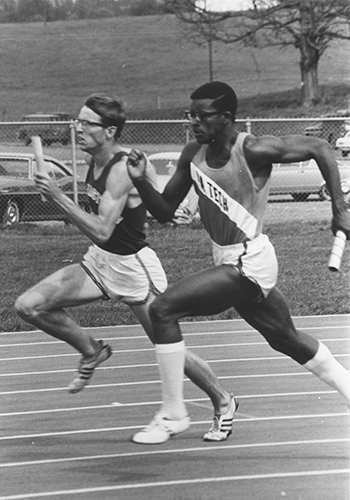

1967 – Jerry Gaines becomes the first black athlete to participate for Tech, earning a full scholarship in track and field

1969 – John Dobbins becomes the first black athlete to play football at Tech, though he didn’t play as a freshman (as per NCAA rules in that era)

1969 – Charlie Lipscomb becomes the first black starter on the basketball team at Tech

1970 – First female intercollegiate athletics team at Tech is organized (swimming)

1977 – Frankie Allen becomes the first black assistant coach at Tech

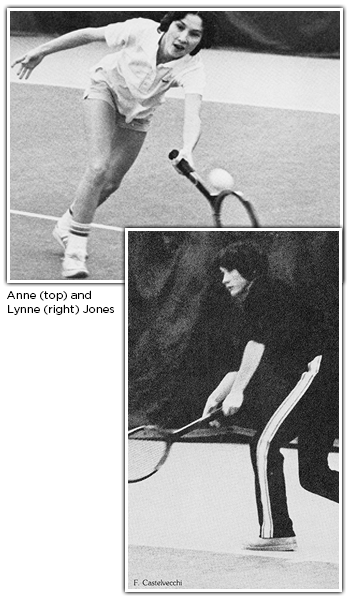

1978 – Anne and Lynne Jones, twin sisters, become the first women to receive scholarships at Tech, joining the women’s tennis team

1979 – Sandy Berry Copeland becomes the first black female to receive a scholarship at Tech, joining the women’s basketball team

1981 – Robert Brown becomes the first African-American football player to earn All-America honors.

1985 – Bruce Smith becomes the school’s first overall top selection in an NFL Draft, going to the Buffalo Bills

1987 – Renee Dennis becomes the first female athlete to have her jersey retired after becoming the all-time leading scorer in women’s basketball

1988 – Frankie Allen becomes the first black head basketball coach

1988 – Bimbo Coles, who would become the school’s all-time leading scorer, becomes the university’s first Olympian

1990 – Gaines became the first black athlete to be inducted into the Virginia Tech Sports Hall of Fame

1993 – Lucy Hawks Banks (track and field) becomes the first female athlete inducted into the Virginia Tech Sports Hall of Fame

1997 – Renee Dennis becomes the first female black athlete to be inducted into the Virginia Tech Sports Hall of Fame

In a lot of ways, Jerry Gaines is the typical Virginia Tech alum. He lives in a modest house in Portsmouth, Virginia, not terribly far from where he was raised. He spent nearly 40 years doing something that he loved and once was named the best in his area at his profession. He got married and raised three children – all of whom went to Tech – and they all love Tech football.

“I can’t stay in the same room as them and watch a game,” Gaines quietly chuckled. “My daughters had never watched a game until they went to Tech. Now they’re calling defenses. I can’t stay in the same room.”

Gaines said this affectionately. He loves his family, loves his life, loves where his career took him and where it continues to take him, and he loves Virginia Tech. After a conversation with this gentle man and gentleman, one can safely make those assumptions.

But he is not the typical Tech alum. He never, ever will be, no matter how much maroon and orange adorns his wardrobe or how vociferously he cheers during a game.

Jerry Gaines is the pioneer that he never wanted to be. In the fall of 1967, exactly 47 years ago, he became the first African-American athlete in the history of Virginia Tech.

“I did not go there to be a pioneer,” Gaines said. “It just happened that way.”

Civil Rights Act and athletics

To understand the challenges Gaines faced as the first African-American student-athlete at Tech, one must first understand the tumultuous decades of the 1950s and 1960s. The United States was coming out of World War II, and the civil rights movement had kicked off. A series of ugly incidents, most related to race, highlighted a roughly 20-year span.

America, though, began the process of overcoming itself in 1964. This past July 2 marked the 50th anniversary of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Signed by President Lyndon B. Johnson, this historical piece of legislation outlawed discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin. It ended segregation in schools, at the workplace and by facilities that served the general public.

To its credit, Virginia Tech started integrating well before 1964. The school started admitting women in 1921, and in 1923, Mary Brumfield became the first woman to receive a degree.

In 1953, the school started admitting African-Americans, with Irving Peddrew III becoming the first African-American admitted to the school. With Peddrew’s admission, the university moved ahead of court orders and became the first historically white, four-year public institution among the 11 states in the former Confederacy to admit a black undergraduate.

Peddrew ended up leaving after his junior year. Charlie Yates became the first African-American to receive a degree from Tech, graduating in 1958 with a degree in mechanical engineering.

The school’s athletics department, though, was a little slower to embrace change. It took 14 years to pass from the time the university started admitting African-Americans before the athletics department welcomed its first African-American with Gaines’ enrollment in 1967.

It came about, really, because of the bravery of a man named Marty Pushkin, Tech’s track and field coach at the time. Pushkin took over the track program in 1964, and he became aware of Gaines’ track exploits by reading the newspapers. He ultimately called Gaines and invited him to campus for a visit, with the intention of giving him a scholarship.

But first he had to sell then-AD Frank Moseley on the idea.

“He had reservations,” said Pushkin, who lives in Morgantown, West Virginia, after retiring as the West Virginia University track coach in 2001, though he still helps with the team as a volunteer coach. “He had concerns about where he [Gaines] was going to live, where he was going to eat, things like that. That seems ridiculous now, but those were the concerns back then.

“But he went along with it. He allowed me to pursue him – and I did.”

Gaines, who had left Crestwood High in Chesapeake, Virginia, to attend integrated Churchland High School in Portsmouth, Virginia, for his final year because it offered him more of an opportunity to showcase his athletic ability, came to Blacksburg for his visit. He knew there were no African-American athletes at Tech at the time, but that didn’t stop him from deciding to come to school at Tech.

“Was it a worry? No,” Gaines said. “My parents had raised us [he and his four siblings] the right way. We were taught to do the right things and to respect others. I never had an issue getting along with people. That was never going to be an issue for me.

“I didn’t go to Virginia Tech to be a pioneer. That was not my motivation. I went there because Tech showed more interest in me than anyone else. They were willing to put their money where their mouth was.”

Overcoming loneliness

Gaines presents an interesting portrayal of his days at Tech. By any account, his was an overwhelming success story. He broke records, he served honorably in the Corps of Cadets and he graduated.

Gaines presents an interesting portrayal of his days at Tech. By any account, his was an overwhelming success story. He broke records, he served honorably in the Corps of Cadets and he graduated.

But he referred to his time at Tech as lonely, a sad reflection of those times. His teammates treated him fairly, but they never invited him out on weekends free from practice or competition. The implication was clear: it was OK to practice together, but not be seen in public with a black guy.

“It was never said, but it was demonstrated,” he said. “Everybody went out and socialized. I spent a lot of time practicing and studying.”

There were a smattering of black students on campus at the time, but Gaines rarely associated with them. Actually, he rarely saw them.

Gaines lived in Miles Hall with the school’s other athletes. Track practices, classes, schoolwork and his Corps responsibilities ate up most of his time. He immersed himself in that rather than seek out company.

“As an athlete, I was isolated,” he said. “The other students hardly ever saw me. Socializing was way down on my list of priorities. With track, my whole year was taken up [between indoor and outdoor seasons]. I don’t know if the other black students understood that.”

Gaines was quick to say that he never experienced overt racism during his time at Tech. But hidden racism certainly existed, at the least in small doses.

Once, while he walked past Lee Hall, which resides on what is now known as Washington Street, a young man dropped an egg on him from an upper-story window. The egg missed Gaines, but it met its demise on the sidewalk, and the remnants splattered on Gaines’ pants. Gaines saw who threw the egg and marched up to the young man’s room to confront him.

To this day, he regrets doing that.

“That was not a good response,” Gaines said. “I’m ashamed that got to me. You see signs and signals [of racism] and it builds, and sometimes, someone does something to push you over the top. I did confront him, and he got an earful from me, but I didn’t feel proud afterward.

“I should have walked away. I needed to get even with my performance on the track. That was my opportunity. I could draw satisfaction from that. It was legal, and it would bring honor to my existence.”

Gaines certainly made a name for himself on the track – though sometimes in spite of the university’s athletics department. Gaines wore glasses, which can be cumbersome during competition, so Pushkin advocated for the purchase of contact lenses. The athletics department said no.

Pushkin also requested a new sweat suit for Gaines after he qualified for the NCAA Championships as a freshman. The athletics department again said no, giving him instead basketball sweats. Gaines refused to wear them.

“I appreciated Marty’s efforts,” Gaines said. “He was very warm and welcoming to me. He pushed to help me. The university did not help.”

Incidents like these, though, were few. In fact, Gaines refuses to dwell on them and instead remembers the ones who reached out at the risk of society’s perceptions during that time.

“For every negative, there were five or six positives,” Gaines said. “That’s’ what kept me going. Often, people I didn’t know would come along and do something nice at the stigma of being seen with me, and I found that to be very encouraging, especially considering the times and the geographic location, with Virginia Tech being in Southwest Virginia.”

Gaines was a curiosity to some of his teammates, many of whom had never been in contact with an African-American. Most came to respect and admire Gaines, though often as time passed. In fact, one of his former teammates sent Gaines a congratulatory letter after President Barack Obama became the first African-American president of the U.S.

“I still have that letter,” Gaines said. “Those are the types of things that make you maroon and orange. It’s like an eternal virus. You’ll always have it.”

As an athlete, Gaines broke the school record in the long jump – a record that had been in place for 40 years. He left Tech with three school records. He still shares the school’s indoor mark in the 120-yard hurdles, and he ranks second in the outdoor long jump and fourth in the indoor long jump. His outdoor mark was just broken by Jeff Artis-Gray last year.

Following his graduation with a degree in Spanish, Gaines served a stint in the Army. Then he became a Spanish teacher at Western Branch High School in Chesapeake, Virginia, where he also coached track. In 1987, he received the High School Coach of the Year honor by the Portsmouth Sports Club, and in 1990, the city of Chesapeake named him the Teacher of the Year. He worked at Western Branch for 29 years and then spent 10 years at Great Bridge High School as an assistant principal before retiring in 2011.

Gaines also was the first African-American inducted into the Virginia Tech Sports Hall of Fame (1990). Interestingly, many of his students never knew of his role in Tech history until after they graduated from high school.

“I never shared that information,” he said. “Very often, my former students will come up to me and say, ‘You never told me,’ and I’ll say, ‘That’s right. I didn’t.’

“They didn’t need to know. I didn’t want that to change the way they looked at me. All I wanted them to know was that there was somebody in their lives who cared deeply about them and their successes.”

Today, Gaines gives motivational speeches, and he’s also written a book entitled “40 Stories High” in which he tells stories about students whom he mentored. He still comes to Blacksburg regularly, as a father of three Tech graduates and a fan of Virginia Tech. He’s also a proud alum, and in his eyes, more so that than a pioneer.

“Very much so,” he said when asked if he was a fan of Virginia Tech despite what he went through during his career. “You can’t graduate from that place and not be.”

Dobbins another pioneer

Former Tech football player John Dobbins passed away in 2003, but to get an indication of how much he loved Virginia Tech, consider the outfit that his longtime wife, Dora, had him dressed in before laying him to rest.

“When he passed, I told my children that I was going to have to put him in a Hokie shirt,” Dora Dobbins said. “When we had the services, I put him in a Hokie sweatshirt, and his casket had the Hokie flag in the background. He was truly a fan. He loved the Hokies.”

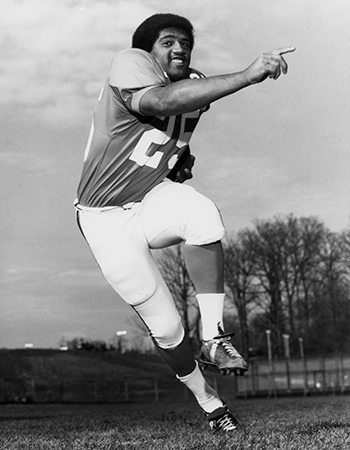

Dobbins, though, was more than a fan or a player. He, like Gaines, was a pioneer. He was the first African-American scholarship football player at Tech.

Few people knew this when he passed away of a heart attack while walking into the Volvo plant in nearby Dublin, Virginia, his place of work for nearly 30 years. The truth is, like Gaines before him, he never saw himself as a pioneer, so he rarely talked about his role in Tech history.

“He was a very quiet man,” Dora Dobbins said. “He didn’t talk a lot about it. He really didn’t. In fact, there were a lot of people who didn’t know it. When he passed away and they [media members] started doing the articles about him and had his picture on TV, people were saying, ‘I didn’t realize that.’ It just wasn’t something he talked about.”

John Dobbins arrived at Tech in the fall of 1969 after being recruited as a running back out of nearby Radford High School by then-head coach Jerry Claiborne. In fact, Dobbins and his high school teammate, Tommy Edwards, a white running back and defensive back, signed to play for the Gobblers live on Claiborne’s coaches’ show.

John Dobbins arrived at Tech in the fall of 1969 after being recruited as a running back out of nearby Radford High School by then-head coach Jerry Claiborne. In fact, Dobbins and his high school teammate, Tommy Edwards, a white running back and defensive back, signed to play for the Gobblers live on Claiborne’s coaches’ show.

This came two years after Gaines broke the color barrier. Dobbins, though, enjoyed a somewhat different experience than Gaines, partly because he arrived two years later and times were changing rapidly in those days. Also, unlike Gaines, Dobbins understood Southwest Virginia in the late 1960s, and he understood Virginia Tech. After all, he lived just 15 minutes from campus.

Dobbins grew up as a Virginia Tech fan, even though the team had no black players and the school had few black students. He knew all about the Gobblers. His high school coaches often brought him to games.

His knowledge of the players and program enabled him to adapt socially a little easier than Gaines. He and his teammates would hang out together, even after he and Dora got married during his junior season. Like Gaines, though, he never really encountered overt acts of racism.

“He had a pretty good experience at Tech,” Dora Dobbins said. “The things that happened were more in high school, things like the name-calling, and when they stopped to eat, they wouldn’t allow blacks to come in. He went through that in high school. I don’t think he went through those experiences at Tech.

“He and [former Tech quarterback] Don Strock were roommates. Dave Strock was a good friend and Bobby Dabbs was, too. They would all come over to our apartment after games, and I would cook. We got along really good. We really did.”

After sitting out his freshman season as required by NCAA rules, Dobbins played the next three years, and he rushed for 705 yards and scored three touchdowns in his career. He amassed 1,261 all-purpose yards.

He wore No. 25 during his playing days at Tech. In a recent conversation with former Tech tailback Kevin Jones, Dora Dobbins and her daughter told Jones that John thought highly of Jones, and it seemed like fate intervened when Jones changed from No. 7 to No. 25 shortly after Dobbins’ passing.

“We were telling Kevin the story, and he got kind of emotional,” Dora said. “He said, ‘You just never know why things happen in life. Now I know why I changed my number to 25.’”

Following his playing days, John Dobbins taught at a pre-vocational school in Roanoke for two years. Then he landed the job at Volvo, where he eventually worked his way into a supervisor’s position.

Dobbins and his wife have bought season tickets since the 1970s. They took their two children to games back then and let them run around on the bleachers because, as Dora laughed, “There was nobody hardly there.”

She kept the season tickets even after Dobbins’ passing. It seemed to be the perfect tribute to a quiet man who loved her and Virginia Tech, one who kept his role as a pioneer to himself.

“Some people go on and on about things, but he just wasn’t like that,” Dora said. “John did so much in the community for underprivileged kids, but he did not want any recognition. He didn’t want people to know that he had bought this child shoes or things like that. If he had any problems at Virginia Tech, then he didn’t tell me about them. He seemed to get along fine with the guys. He had a good experience.

“He liked Tech. He was a big fan.”

Women’s rise to prominence in Tech athletics

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 not only prohibited racial discrimination, but also discrimination based on sex. This was designed to ensure that women would have a way to fight discrimination in the work place, just as minorities would be able to fight racial discrimination.

Eight years after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed, another law entitled Title IX was passed. This law requires gender equity for boys and girls in every educational program that receives federal funding. Most people view Title IX through the prism of college athletics, but this law addresses many other areas, too (access to higher education, career education, education for pregnant and parenting students, employment, etc.).

Virginia Tech began introducing women’s sports not long after the Civil Rights Act of 1964 passed. In 1967, the school hired its first full-time female health and physical education instructor, Shirley Ann Mell, who organized a women’s intramural program. In 1970, the school sanctioned its first varsity sport – swimming.

In 1976, the university initiated a search for its first director of women’s intercollegiate athletics and hired Jo Kafer, who was expected to direct the women’s intercollegiate program, coach, and lead the development of women’s sports. She oversaw basketball, swimming, tennis, and track and field, and she later oversaw volleyball and field hockey after the university added those two sports in 1977.

Many today consider her the pioneer of Tech’s women’s sports.

“She was the one who really got women’s sports going,” Anne Jones said.

Jones and her twin sister, Lynne, were the first two female athletes at Tech to receive scholarship aid. The War, West Virginia, natives came to Tech largely because the aid they received – and Kafer, who also coached field hockey, was the one who recruited them and offered them the partial scholarships even though she wasn’t the tennis coach.

Jones and her twin sister, Lynne, were the first two female athletes at Tech to receive scholarship aid. The War, West Virginia, natives came to Tech largely because the aid they received – and Kafer, who also coached field hockey, was the one who recruited them and offered them the partial scholarships even though she wasn’t the tennis coach.

“That’s the only school we really wanted to come to,” Anne Jones said. “We also looked at Marshall and the University of Kentucky. My father went to Marshall, so we had to look at Marshall.

“Our first goal was to keep playing tennis because we just loved tennis, but I wouldn’t say the scholarship was the goal. It was definitely something we wanted. It helped us come out of state. We probably wouldn’t have come to Virginia Tech otherwise. So in that respect, we really wanted the scholarship from Tech. We had been down a couple of times for football games with our father, and we loved the school.”

Anne Jones went on to become a terrific tennis player at Tech, winning nearly 65 percent of her matches during her career. She enjoyed her time at Tech, though the school had only modest tennis facilities, and both the men’s team and women’s team practiced at night because the university rented the courts during the day and wanted to keep that revenue stream. There was also little in the way of locker room amenities.

“We didn’t have a locker room,” Jones said. “The women’s training room was down on the second floor [of the Jamerson Athletics Center], and it was small, and there was a locker room off the end of that. All the women’s sports shared that except for women’s basketball. We shared the locker room and the training room.”

Jones graduated in 1981 with a degree in health and physical education. In 1984, she got her master’s degree from Tech in exercise physiology.

Not long after she got her master’s, she got a call from Kafer. She was working a tennis camp, and Kafer wanted to know if Jones would be interested in the women’s tennis coaching position at Tech.

In September of 1984, Jones became a pioneer for the second time – she was the first full-time women’s tennis coach in Tech history.

“Some of the other coaches had been teaching or working in other areas,” Jones said. “I was the first full-time women’s tennis coach – no teaching or anything like that. I made $7,000 a year.”

Jones coached at Tech for 16 years, winning 260 matches and losing just 159 – she’s the winningest women’s tennis coach in Tech history. She also led the Hokies to the Atlantic 10 Conference title five times and earned Coach of the Year honors five times. She retired following the 2000 season.

Her playing career and coaching tenure coincided with some of the biggest changes in regards to women’s sports at Tech. The athletics department started putting more resources into its women’s programs – and the subsequent results were championships, as Jones can attest.

“We ended up with better facilities and more funding,” she said. “We were able to travel more, and we got an assistant coach. We were able to give the full compliment of scholarships.”

Tech’s moves into the BIG EAST and later the ACC for athletics resulted in substantial increases in financial payouts from those conferences. That money has been used to help all women’s sports, and the athletics department is one of a small group of schools in full compliance with Title IX standards. And last year, then-AD Jim Weaver added another women’s sport – golf – to the slate.

“I think Tech has done a good job,” Jones said. “I really do. I imagine there are some people who would disagree with that, but I think, as far as coming along and the quality of the Olympic sports, I think they’ve done a good job.”

Watching the next generation

Fifty years ago, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 changed America forever, and gradually, played a role in changing the landscape of college athletics. It opened doors, not just ones that had been shut, but also locked.

On Nov. 1, at halftime of Tech’s football game against Boston College, athletics department officials took the time to recognize Gaines, the Dobbins family and the Jones twins for their roles in shaping the history of Tech athletics. Michael Vick, Bruce Smith and Kevin Jones came to prominence because of people like Gaines and Dobbins. Amy Wetzel, Angela Tincher and Queen Harrison received scholarships as female superstar athletes because the Jones twins broke that barrier.

If nothing else, the recognition during the BC game served to educate Tech fans, alums and students, many of whom know nothing, or very little, about these trailblazers.

Of course, that doesn’t really bother them. They don’t view themselves in that light anyway.

“I never think of it that way, but we probably were,” Anne Jones said.

“That’s just the way it turned out,” Gaines said. “ I did not wish to make it a big deal. I wanted to be known as someone who came along and added something without leaving dirty footprints.”

None of these individuals left dirty footprints. On the contrary, in fact.

But they certainly left large ones, ones that can never be filled. And hopefully, the coming generations appreciate that.

For updates on Virginia Tech Athletics, follow the Hokies on Twitter Follow @hokiesports

Ticket Market Place

Ticket Market Place

Sports Radio Network |

Sports Radio Network |  Travel Center & Info

Travel Center & Info